In 1870, when Lt. Gen. Butler at the request of the Canadian government travelled along the North Saskatchewan River on horseback, canoe and later dog sled from Winnipeg to Rocky Mountain House west of Edmonton, he carried with him a supply of smallpox vaccine which Hudson Bay officers administered to the surviving Indian tribes who had been all but wiped out by the disease. Over a period of some fifty years, ninety percent of the Blackfoot, Cree, Dakota, Chipewyan and other tribes in the Saskatchewan region had been killed by the scourge. Smallpox is often called the white man’s disease but it doesn't care a whit about race or ethnic origin. It is one of the most contagious and loathsome diseases ever to menace humanity. It first appeared in Egypt in the 3rd century BC.

"No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous," wrote Edgar Allan Poe. "Blood was its avatar and its seal - the redness and the horror of blood. There were sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores, with dissolution. The scarlet stains upon the body and especially upon the face of the victim were the pest ban which shut him out from the aid and from the sympathy of his fellow-men."

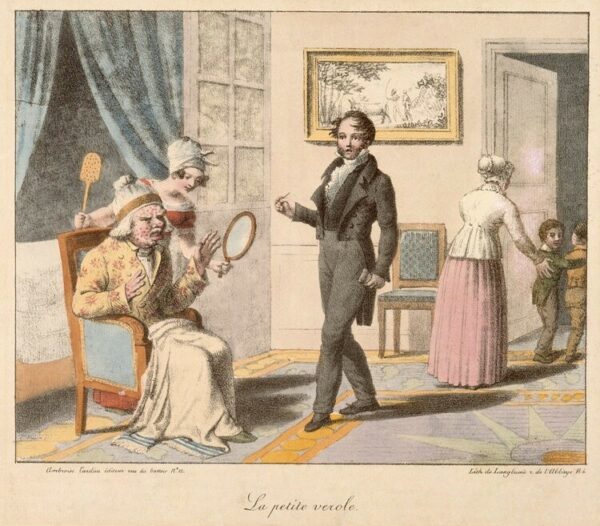

The vaccine brought by Butler had been discovered by Edward Jenner in 1796 who had observed that milkmaids who had previously caught cowpox did not catch the smallpox virus. He was able to prove that contact with cowpox had actually inoculated the women against the smallpox virus. By the 1850s, the vaccine was well known and busy saving lives whenever there was an outbreak. Unfortunately, not everyone was in favour of vaccinating the population as is the case today with the COVID vaccine.

The smallpox plague arrived in Montreal by train from Chicago. A Pullman conductor on the Grand Trunk Railway, George Longley, brought the disease with him in February 1885. He arrived feverish and covered with fiery eruptions on his hands, face, and arms. The story is that he was rushed to the Montreal General Hospital where a physician quickly diagnosed him with smallpox but refused to admit him. He then took refuge in the Hôtel-Dieu hospital run by nuns and eventually survived, but his bedding infected an Acadian girl who worked in the hospital laundry. Soon smallpox was rampant among the patients and staff at the hospital and couldn't be contained. Panic set in and the board of health made a terrible decision. They closed the hospital and discharged all the sick patients setting the virus loose among the population of the city.

At the time Montreal was a sophisticated modern city and the largest in Canada. The medical profession knew all about epidemics and how to contain them. Vaccines were made available to the population and anglophones quickly rushed to get vaccinated. The francophone population on the other hand were immediately hostile to any attempt to help them or contain the disease. As the number of smallpox cases rose, the English newspapers started to sound the alarm. Many anglophone factory owners advocated compulsory vaccination for their francophone staff, leading some workers to view vaccination as a weapon against the French.

Anti-vaccine campaigns were launched in the city. The medical staff at vaccine centres were called "charlatans" and “trying to poison our children" in the press. A famous anti-vaxxer at the time was the respected physician, Dr Joseph Coderre, who spoke out strongly against vaccination in large part because two of his own children had died shortly after being vaccinated by tainted vaccine. He claimed that the smallpox vaccine would not prevent the disease and might give one syphilis. The fact that the city's original vaccination program had to be suspended due to tainted vaccine did not help the cause.

Montreal soon became known across North America and Europe as a plague city to be avoided at all costs (a bit like Seville and London during the Black Death). As the long hot summer of 1885 dragged on, smallpox victims and their children gathered in the streets with scabs still contagious. Every night bodies were collected and hauled away in wagons to the Côte des Neiges cemetery for burial. Attempts by the public health authorities to enforce vaccination or isolate smallpox victims or even to carry away the dead were often met with resistance and riots. Constables were assaulted as they tried to remove corpses from the worst-infected neighbourhoods. Quebec strongman Louis Cyr was recruited to haul infected tenement dwellers off to the hospitals.

On September 28 an unruly mob stalked the streets hurling stones and denouncing the authorities. The Catholic Church hierarchy eventually came down in favour of vaccination as did French newspapers in the city, but not in time to save large numbers of French Canadians. The Red Death ran its course into November killing more than 5,800 people (around 3% of the population) and disfiguring some 13,000, before it exhausted its supply of unvaccinated hosts. Nine out of ten victims were French Canadians, most of them children.

The vast majority of Montreal’s anglophones were barely touched by the epidemic while the poorer francophone population, who often resisted vaccination, paid a heavy price. "It was the last uncontrolled holocaust of smallpox in a modern city," wrote Michael Bliss in his 1991 book, Plague: A Story of Smallpox in Montreal. The disease today has become something of an historical curiosity due to vaccination. No Canadian has contracted smallpox since 1944, and with the death of the world’s last smallpox carrier in 1978, the disease appears to have disappeared forever.

*Originally posted in July 2021

Comments ()